Introducing our curious collections

When you think about the National Trust’s collections, I wonder what comes to mind first? It might be the paintings - more than 13,000 of them - including masterpieces by artists such as Canaletto, Rembrandt, Gainsborough and Reynolds. It might be the internationally-significant Thomas Chippendale furniture, or the precious Chinese ceramics, or some of the half a million books in Trust libraries. But what about rocking horses, or scrubbing brushes, or jewellery? How about a Dalek (or two!), taxidermy fish or Bakelite electric “hot water” bottles? The National Trust collection is all this and more and part of my job as Assistant Curator for Collections is to help share these riches with as many people as possible.

We look after over one million items at over 200 places across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The collection spans continents and centuries, with everything from Egyptian tablets to 21st century sculpture. But what makes our collections particularly special is their context. Unlike many museums, we often look after these objects in the places they were made or bought for and used in. This means we can tell an even richer story about these objects or the people who commissioned, bought or used them. And every object tells a story, whether it is a Rembrandt self-portrait, the paint box used by Winston Churchill or one of the thousands of everyday items that are part of the lives of our properties. And then, there are the quirky, intriguing or downright bizarre objects…

5 Intriguing items

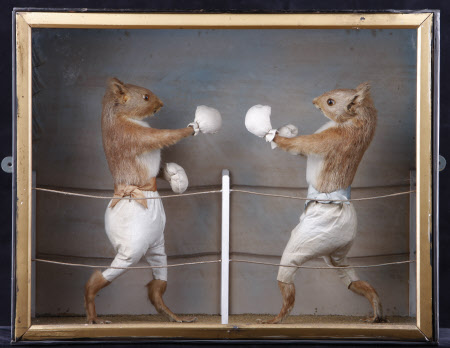

We might find this distasteful today, particularly because red squirrels are under threat as a species. But Victorians were intrigued by this ‘anthropomorphic taxidermy’ – setting up stuffed animals in poses as if they were miniature humans. Several taxidermy exhibits were displayed in the Great Exhibition of 1851, including frogs having a shave and kittens serving tea (created by German taxidermist Hermann Ploucquet). Squirrels and frogs were often used, since their shapes and body proportions lend themselves to imitating humans, and they were available in good numbers; red squirrels were shot by local foresters protecting their trees, in the days before grey squirrels became widespread.

The house at Snowshill was soon full of Wade’s collection and he spent many hours there arranging and labelling objects. In the meantime, he lived out of the old cottage in the courtyard, where you can now find this wooden cat. The cat was a gift from Wade’s friend, Professor Albert Richardson. Richardson apparently felt that Wade needed company at Snowshill but didn’t think his friend was responsible enough to look after a real pet. So, he presented Wade with a life-sized wooden cat. White with black spots, the cat also had whiskers and eyelashes and stood on a rug next to his fire, an empty food bowl in front of him. Despite of his friend’s doubts, Wade did in fact look after his wooden pet, replacing its whiskers every year.

Find out more

- National Trust Collections - Explore more treasures*

- Blog - Discover more curious collections from around the country

*To find more on the objects mentioned here search for their catalogue numbers:

- Marquess of Anglesey’s wooden leg - NT 147435

- Boxing Squirrels - NT 836091.1-5

- Fire extinguisher grenades - NT 1145704.4

- Lord Nuffield’s appendix - NT 1651877

- Charles Paget Wade’s pet cat - NT 1332424